This text was first published in the magazine TIERBEFREIUNG, in October 2022, in German. It was a theme issue (#116) about disability and ableism.

__________________________________

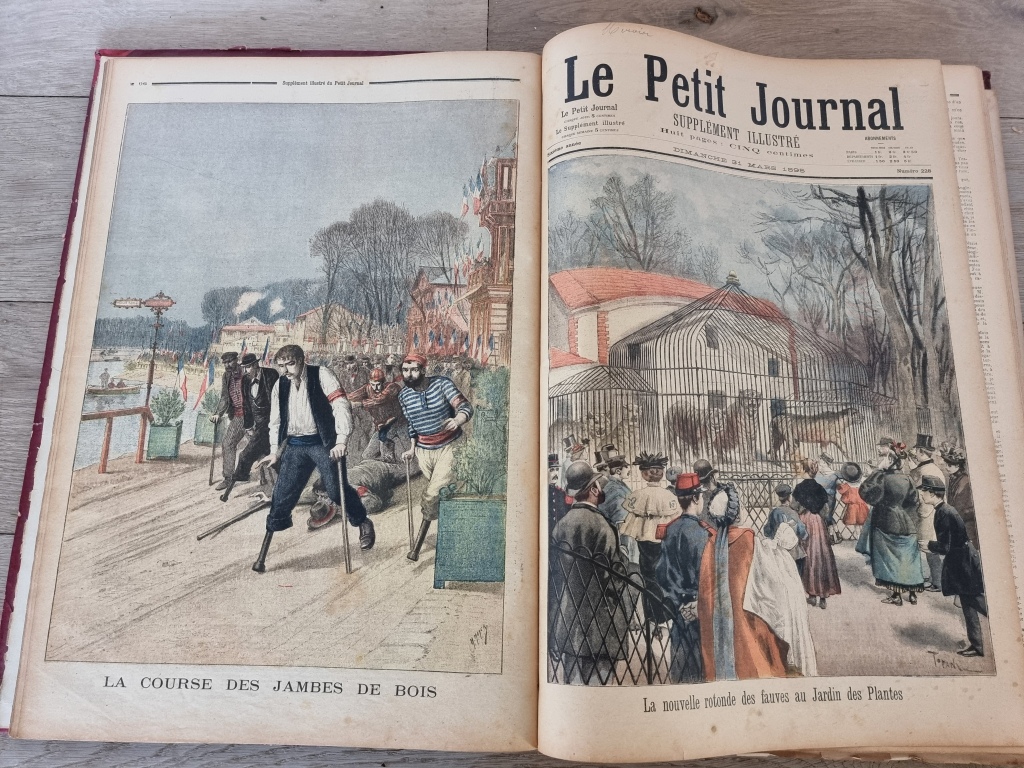

As I was cleaning out a closet recently, I came across a collection of French newspapers from the end of the 19th century, bundled together in book format. The collection contains the illustrated supplements of ‘Le Petit Journal’ of 1895, and probably came in my possession through my father or grandparents.

I randomly browsed through it and stumbled upon two images covering two opposite pages. On the left a drawing of men with wooden prosthetic legs, walking with a cane, engaged in what appears to be a race. One of the persons has fallen down, and seems to be at risk from being run over by those coming from behind him. Going by their clothes, all of the participants seem to be men and predominantly from working class backgrounds. The image is titled ‘La course des jambes de bois’ (= the race of the wooden legs). The adjacent image on the right is the cover image of the following edition, and shows a drawing of a zoo, with in the background five tigers enclosed in barren Victorian looking cages. There’s a small crowd – seemingly upper class going by the clothes and hats – gathered in front of the cages, looking at the tigers. The image is titled: ‘La nouvelle rotonde des fauves, au Jardin des Plantes’ ( = the new pavilion of the wild animals, at the Garden of Plants).

Two different scenes, and yet underneath the surface lie similarities. Without any historical background, one could interpret ‘the race of the wooden legs’ as an early manifestation of paralympic sports and respect for disabled athleticism. More probable, and deducting from the small article about it in the newspaper and the scornful title, is that the organisation of the race was instigated by a longing for spectacle, curiosity and entertainment. And in that respect it bears similarities with the spectacle of gazing at wild animals in the image on the right. Both disabled persons and other animals reduced to spectacle objects, used for entertainment. On a side-note: it is probably also no coincidence that the spectators look (going by their attire) mainly to be from upper and ruling class and the wooden leg racers mainly to be working class.

In this same period (late 19th beginning of 20th century), persons with highly visible ‘extraordinary’ features like women with facial and body hair, conjoined twins, smaller or larger than average length and so forth, were also put on display in so-called ‘freak shows’ – sometimes travelling together with ‘exotic’ wild animals in roadside zoos and circuses. Although there are records of disabled people using such employment in an empowering way, they were often coerced into participating and exposed to exploitation, belittlement and ridicule. They not only shared the circus stage with other animals, but their stage names reflected how they were ideological ranked as animals: being referred to as the baboon woman, the elephant man or the snake man; and hence devalued to being subhuman. At the beginning of the 21ste century, people still go to zoos and animal parks to gaze at exotics animals, although now the entertainment aspect is framed as being part of nature conservation and helping to prevent animal species going extinct. ‘Freak shows’ are looked upon with dismay and considered an example of an ableist past. But is it really a thing from the past? Disabled people are no longer travelling in circus shows to perform tricks and be gazed at, but disabled bodies are still gazed at in television shows such as ‘embarrassing bodies’ or pseudo-documentaries about the lives of disabled persons or the medical procedures necessary to ‘fix’ them. Disabled athletes are now acknowledged as professional athletes and are competing in organised leagues, but hardly receive the same recognition and support as their fellow abled bodied athletes. The Paralympics are still organised separately from the Olympics, and many disability rights advocates claim that real inclusion can only be achieved when they are held together as one event.

The ‘freak shows’ from a century ago are just one example of how ableism and speciesism intersect. There are so many more instances where ableism and speciesism intersect, overlap or are connected. Consider the environmental impact of animal agroindustry which in its turn has serious health implications for the people living in that environment. Consider the psychological and physical toll on slaughterhouse workers, making many of them disabled. The Animal Industrial Complex depends on cheap labour, and exploits not only animals, but also humans. Speciesism in itself can be seen as a form of ableism, because it is discrimination of other animals because they do not possess certain abilities.

Throughout history, several abilities have been the demarcation line to give moral status to some and deny it to others: being able to speak, being able to reason, eyes that face forward, walking on two legs, etc. This also had implications for humans who do not possess those abilities (who cannot speak, who cannot see, who cannot reason): they were or are still seen as less human. Disabled people were at one point even seen as the missing link between humans and other animals.

In 2018, inspired by the groundbreaking book Beast of Burden by Sunaura Taylor (2017) I launched the platform Crip Humanimal as a space to specifically address the interconnections between ableism and speciesism, animality and (dis)ability. ‘Crip’ refers to the historically derogatory term ‘cripple’, but is now an insider term for disability culture or disability identity. Humanimal is a conjunction between human and animal. It is about the oppression of humans and other animals, and how these overlap, intersect and are connected.

Crip Humanimal is not so much a blog about my own story of living as a disabled vegan, but a platform to share and archive resources about disability and critical animal studies, to center stories of disabled vegans and also highlight stories of disabled animals. And also a place to address the ableism, bodyshaming and healthshaming in the vegan and animal rights movement.

As I am living in criptime myself, the time and resources I can spend on exploring these issues and advocating for disability rights and animal rights is limited. Anyone is welcome to submit a piece to Crip Humanimal, or contribute in another way.

Geertrui Cazaux

0 comments on “Gazing at wooden legs and caged tigers – ‘Le Petit Journal’”